CoachPinkston

January 8, 2026

If you’ve ever said to yourself—or heard an athlete say—

“I tried to change, but I failed. Something must be wrong with me.” You’re not alone.

Every season, I work with athletes who desperately want to improve their confidence, consistency, discipline, or mindset. Coaches want culture change. Parents want better habits at home. And when change doesn’t stick, the story we tell ourselves is almost always the same:

“I must not want it enough.”

“I’m not tough enough.”

“I just don’t have the self-control.”

Here’s the truth—and this is good news:

There is nothing wrong with you.

There is a better, more effective way to create change.

That’s the central theme explored in a powerful conversation between learning expert Trevor Ragan and behavioral scientist Katy Milkman, professor at the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania and author of the book How to Change.

Their message aligns perfectly with what elite performance psychology teaches us in sport:

Change doesn’t fail because of motivation.

It fails because we’re using the wrong tool for the problem.

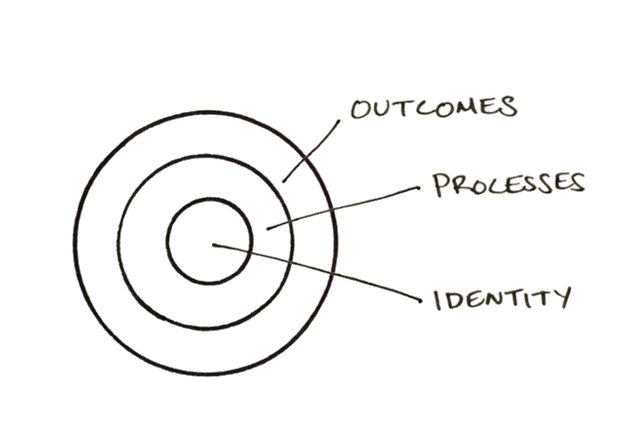

Most athletes are taught some version of this:

Those ideas aren’t wrong—they’re just incomplete.

The mistake is assuming that one strategy works for every problem. In reality, behavior change is diagnosis-dependent. If you don’t understand what is blocking progress, even the best tools won’t work.

As Milkman explains, habits are powerful—but they’re only one small piece of a much bigger puzzle.

According to decades of behavioral science research, most failed change efforts fall into one (or more) of these categories:

1. Getting started

2. Impulsivity

3. Procrastination

4. Forgetfulness

5. Laziness

6. Low confidence

7. Conformity (social pressure)

Let’s translate these into the sports world.

If an athlete doesn’t believe change is possible, nothing else matters.

This is where the research of Carol Dweck becomes essential. Her work on growth mindset shows that when athletes believe skills can be developed, failure becomes feedback—not a verdict.

Language shapes belief. Praise effort, learning, and strategies—not just outcomes.

One of the most powerful (and overlooked) confidence builders is teaching.

Research shows that when people coach others toward a goal:

In one randomized controlled trial, high school students who spent just 10 minutes giving study advice to younger peers significantly improved their own GPA.

Have athletes mentor younger teammates. Confidence grows fastest when responsibility is shared.

Fresh starts matter more than we think.

Research on the “fresh start effect” shows people are more likely to initiate change:

Don’t dismiss “new beginnings” as soft psychology. Use them strategically.

Impulsivity: Why Willpower Isn’t the Answer

Impulsivity is driven by present bias: we overvalue what feels good now and undervalue future benefits.

That’s why athletes:

Temptation Bundling

Pair something you should do with something you want to do.

Environment Design

Remove cues that trigger poor choices.

You can’t rely on willpower in the moment—you have to win the battle before it starts.

Procrastination isn’t laziness—it’s delayed discomfort.

The most effective solution? Commitment devices.

Examples:

Research shows people are dramatically more successful when future decisions are pre-committed.

This is why practice schedules, accountability partners, and competition calendars work.

Some behaviors happen too infrequently to become habits.

The solution isn’t “try harder”—it’s:

Assume you’ll forget—and design systems that save you.

Humans are efficiency machines. We take the path of least resistance.

The secret is aligning what’s easiest with what’s best.

Defaults matter. Studies show changing the default option—from opt-in to opt-out—can shift behavior by 40% or more.

What’s the easiest choice in your environment right now?

Social influence is one of the strongest forces in behavior change.

If your environment normalizes:

Culture isn’t what you say—it’s what’s reinforced daily.

Elite teams don’t always do more—they do better with the reps they already have.

One Olympic program used “declaration days,” where athletes publicly committed to one skill focus for two weeks.

The result?

More intentional reps. More growth. Same practice time.

“For the next two weeks, I’m working to get a little better at ______.”

Change isn’t about toughness.

It’s not about wanting it more.

And it’s definitely not about shaming yourself.

When you diagnose the real obstacle and apply the right tool, progress becomes inevitable.

If you’re an athlete, coach, or sport parent who wants science-backed mental performance tools you can actually apply: